Judith Fein visits a treasured island

By Judith Fein

Most travelers to Curaçao, one of the Dutch islands in the Caribbean, expect to find sand but they don’t expect to find it indoors, covering the floor of a synagogue. Mikve Israel-Emanuel is no ordinary synagogue; built in 1732, this Sephardic house of worship is the oldest synagogue in continuous use in the Western hemisphere.

It was founded by Jews who fled the cruel clutches of the Inquisition in Spain and Portugal and arrived in tolerant Amsterdam. Some of the adventurous ones took to the high seas to seek their fortunes in Curaçao. There, they established a congregation in 1651 which was called “the mother congregation” because they survived, prospered, and were able to send people and money to found Sephardic synagogues in the Caribbean, South America and the USA (in Newport, Rhode Island).

The synagogue they built in Curaçao recalls their chilling underground life as Jews in Iberia. On the surface, they had converted to Catholicism, but under penalty of death they observed the laws of Moses and conducted secret prayer services in their attics or other remote rooms in their houses. In order to muffle their footsteps so they wouldn’t be detected, they covered the floors of the rooms with sand.

The sand that covers the floor of Mikve Israel-Emanuel recalls those horrific times, and also represents the exodus from Egypt, when the Jews wandered in the desert for forty years. According to synagogue former president René Maduro, there is also symbolism inherent in the Sephardic-style layout of the synagogue with its pulpit in the center and seats spread throughout the room. “The sand of the desert is all around, the tabernacle is in the middle and Israel is around the sides,” he said.

Maduro, an ebullient, energetic, knowledgeable man, adds yet another layer of meaning. “You remember in the Torah God said to Abraham, ‘I will multiply your seeds like the stars of heaven and the sands of the seashore.’ And Abraham laughed because he was 99 years old and he had no children. The sand represents that promise.”

The synagogue boasts eighteen Torah scrolls which are more than three hundred years old. Several go back to the 1400s, which means that they must have come with the Sephardim who fled Spain in 1492 after the Edict of Expulsion. In modern times, thirty years ago, the four central columns of the synagogue were named to honor the Biblical matriarchs–Sarah, Rebecca, Leah, and Rachel.

Visitors to Curaçao are invited to attend Friday night and Saturday morning services, and they are welcome to participate in the annual Passover meal in the courtyard of the legendary synagogue. Of course there is a stringent security check, but concerns for safety are nothing new; it is an unfortunate part of the still-unfolding crypto Judaic story.

On a hot, humid Friday night in September, a few tourists joined the thirty congregants (which represents about ten per cent of the congregation living on the island) for the Sabbath service. “It is so moving to be here, standing in sand, praying” a woman from California said. “It’s really ancient and primal. I feel so much emotion I could just cry.” When the dark, wooden doors of the ark were opened to display the Torah scrolls, tears streamed down her cheeks.

The Curaçao hosts were hospitable and openhearted, directing the much-needed floor fans towards visitors and inviting them to an afterservice kiddush. More than seventy per cent of the synagogue’s members are Sephardic Jews who are proud descendants of the first families in Curaçao. The original Jewish settlers spoke Portuguese, but today congregation members converse in fluent Dutch, English, Spanish, and Papiamento (the local Curaçao language) in addition to a host of other tongues. One of the hallmarks of their success was their ability to adapt to the culture and the world around them.

The synagogue complex also boasts a Jewish Historical Cultural Museum (closed on Sabbaths) which includes the remnants of a mikvah, or ritual bath, from 1728. The evocative museum is bursting with precious artifacts–still used today– from the early Sephardic community. There are tall, wooden circumcision chairs, an extensive shofar collection, a Passover table, baby naming and circumcision dresses (they resemble christening clothes). Glass cases contain silver spice boxes and candlesticks, Hanukah lamps, and intricately embroidered Torah covers. For the mourning holiday of Tisha B’av, unusual and touching customs prevail among the Sephardim; the Torah is draped in black, the rabbi used to wear a black hat, and even the “yad,” which is used as a pointer by the Torah reader, is black. When they are not in use, the items are kept in the museum.

Another curiosity is a huge silver platter that is bashed and battered. Unlike the Ashkenazi, or Eastern European custom of stepping on a glass during a wedding, the Sephardim of Curaçao threw the glass into the platter, and the marks remain forever.

René Maduro proudly tells tourists about the synagogue’s history, which includes the obligatory schism over religious observances. Mikve Israel was originally an Orthodox synagogue, and a breakaway group built the rival Reform Temple Emanuel in 1864. Over time, the two groups have miraculously found a compromise and they re-united in 1964 to form the Reconstructionist congregation Mikve Israel-Emanuel, in the original 1732 building. They are devoted to honoring their ancestors, their temple and their religion, but they are subject to complaints from visiting American Jews who criticize them for not having an active ritual bath or keeping kosher.

Not far from the synagogue (everything is easily accessible on the 35 mile-long island) is one of the most remarkable Jewish cemeteries in the world, founded in 1658. The holy terrain, with its 2,500 aboveground historic tombstones, is in the shadow of the oil refinery built by Shell; although the community put up a fight, commerce won over sanctity. Grey smoke belches from the smokestacks and erodes the priceless tombstones that continue to bear silent witness to a proud and successful Jewish settlement.

The cemetery’s name, Beit Haim or House of the Living, recalls the Jewish belief in the afterlife. The resting place for over 5,000 souls (2,500 of the stones are no longer visible) is prized for its ornately sculpted marble memorial slabs that go back to the seventeenth century. One of the main recurring symbols is a hand with an axe that chops down a tree in its prime; the tree represents the life of the deceased. When a baby died (which one out of three did), the axe fells a flower and the grief is almost palpable across the centuries.

For more information about Kura Hulanda: www.kurahulanda.com

General Curaçao information: www.curaco-tourism.com

All Jewish sites can be accessed by taxi, public transportation or rental car, and Taber Tours in Curaçao also offers tours to Jewish sites. Telephone: +599 9 737 6713 Email: Tabertrs@Cura.net

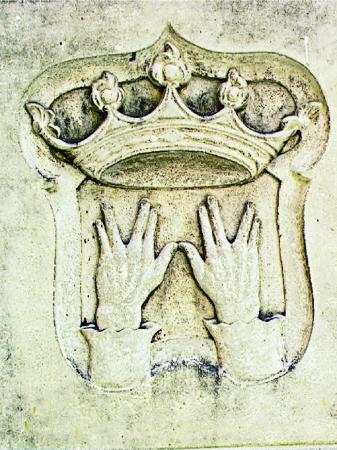

Sometimes a person’s profession is remembered, like ships for merchants, and other times the dead person’s name is connected to his Biblical namesake. When a David died, the stone carving might depict the Biblical David, playing a harp or pitting his might and wits against Goliath. A Jacob lies beneath a marble carving of Jacob’s ladder, and a Rachel who died in childbirth is remembered with a striking deathbed scene that harkens back to Biblical Rachel, who died giving birth to Benjamin. The Cohens, or priest class, lie beneath outstretched hands in the position of the priestly blessing and the Levis, who assisted in the ancient Temple, may be depicted as ritually washing the hands of the Cohens. There are also non-Jewish symbols like cherubs, skulls and crossbones, and an hourglass; the crypto Jews of Iberia and the Jews who came to Curaçao were integrated into the life of the community around them and often adopted the tastes and styles of their neighbors.

At the far end of the cemetery are two white, non-descript buildings. One of them has two stories and is for the priestly Cohens who, for reasons of purity, are not allowed to have contact with the dead. Instead, they can climb to the second floor and watch the somber funerary proceedings through a large window. The other building is to accommodate an old Sephardic tradition. The coffin of the deceased, surrounded by seven candles, is laid on a bier in the center of the building and is circled seven times by mourners reciting psalms before the coffin is placed in the ground.

Not far away is a newer Jewish cemetery from 1880 that also has above-ground neo-Classical tombstones over the graves. Besides seeing old Sephardic customs in the two cemeteries, visitors can observe the changing tastes of funerary fashion through the centuries. The cemeteries, like the synagogue, attract tourists of every religious persuasion and from countries around the globe. According to Maduro, the synagogue is the most visited building on the island.

A drive through the Scharloo area of Willemstad (the capital of Curaçao) provides other glimpses into the Sephardic past. The multicolored, wedding-cake-like mansions were owned by many wealthy Jews and white Protestants. They built their houses on the water so they could row to the nearby town center. The cost of maintaining the palatial residences became prohibitive early in the last century and their owners, who moved to suburbia, abandoned them. Today many have been restored and serve as offices for international companies and banks.

At one time, Sephardic Jews made up half of the white population of Curaçao, and today their presence is felt at every level of society. The owner of the famed Senior Curaçao liqueur comes from one of the old families, and the descendants of the crypto Jews own many of the present businesses and buildings.

One of the most intriguing Curaçao residents with Jewish ancestry is Jacob Gelt Dekker. His father was a Dutch Holocaust survivor. Dekker made a fortune in Holland by selling his onehour photo franchise to Kodak and his Budget Rent-A-Car franchise to a major bank. With the profits, he moved to Curaçao, purchased 196 acres of old buildings and a plantation, restored and remodeled them and opened the luxurious l96-acre Kura Hulanda resort.

During the remodeling of Kura Hulanda, Dekker discovered that one of the old buildings was a principal site of slave trading on the island. He began to research slavery, and realized that the total picture is much more complex than most people suspect. In ten months, Dekker had put together an amazing museum complex, which is open to the public. In one section, through exhibits and artifacts, he tells the intricate and shameful story of selling and trading human flesh. It is the most comprehensive slave museum in the Caribbean, if not in the world. Other rooms include a world-class Mesopota-mian collection, scores of Benin bronzes from Africa, one-of-a-kind African sculptures, Japanese woodblocks and a jazz section. Dekker himself is a scholar, pilot, dentist, linguist, histologist, businessman and collector. He is also an outspoken proponent of religious, intellectual and sexual tolerance, and welcomes gay tourists at his resort.

An important attribute of the Jews of Curaçao is that they never isolated themselves from the larger community, and they are an integral and integrated part of the island. For 350 years they have contributed “tsedaka” or charity to all their fellow countrymen, regardless of religion, and also assured the upkeep of their world-famous synagogue and cemeteries. Their lives and their buildings provide a precious look at forgotten customs of the courageous and beleaguered crypto Sephardic Jews.

IF YOU GO:

Mikve Israel-Emmanuel is open to the public Monday to Friday (except holidays) 9am-11.45am and 2:30pm-4:45 pm. For more information: www.snoa.com or info@snoa.com.

For more information about Kura Hulanda: www.kurahulanda.com

General Curaçao information: www.curaco-tourism.com

All Jewish sites can be accessed by taxi, public transportation or rental car, and Taber Tours in Curaçao also offers tours to Jewish sites. Telephone: +599 9 737 6713 Email: Tabertrs@Cura.net

Judith Fein is an award-winning international travel journalist who has contributed to more than 100 publications. She is the author of Life Is A Trip: The Transformative Magic Of Travel and the new The Spoon From Minkowitz: A Bittersweet Roots Journey To Ancestral Lands. Her website is: www.globaladventure.us