The Holy City of Jerusalem, sacred to the world’s three great monotheistic religions, naturally attracts millions of tourists every year. Most cities whose economy thrives on tourism have double-decker buses that follow circular routes with stops at all the major sightseeing attractions; Jerusalem is no exception. The Egged bus company’s Route 99 runs in a two hour loop through both East and West Jerusalem, with a hop-on, hop-off feature enabling passengers to get on and off throughout the day. A taped audio guide in eight languages enhances the

impressive visual experience.

By Malcolm Ginsberg

The Holy City of Jerusalem, sacred to the world’s three great monotheistic religions, naturally attracts millions of tourists every year. Most cities whose economy thrives on tourism have double-decker buses that follow circular routes with stops at all the major sightseeing attractions; Jerusalem is no exception. The Egged bus company’s Route 99 runs in a two hour loop through both East and West Jerusalem, with a hop-on, hop-off feature enabling passengers to get on and off throughout the day. A taped audio guide in eight languages enhances the

impressive visual experience.

By Malcolm Ginsberg

While certainly recommended to any tourist as an excellent

introduction to the city, Jerusalem’s Route 99 has a particular

problem: a great part of downtown has been off-limits to vehicular

traffic since the new light rail system was inaugurated in

2012. Fortunately, the light rail is now a terrific complement to

the round-robin bus tour – and quite a bit cheaper.

For six shekels ($1.70), one can buy a ticket that is good

for three hours on the train; passengers can “jump on and

jump off” at will during this time period. Since the light

rail is meant primarily for residents and commuters, there

is obviously no audio guide. But any decent guidebook –

or downloadable city guide app – will explain the sights

along the route.

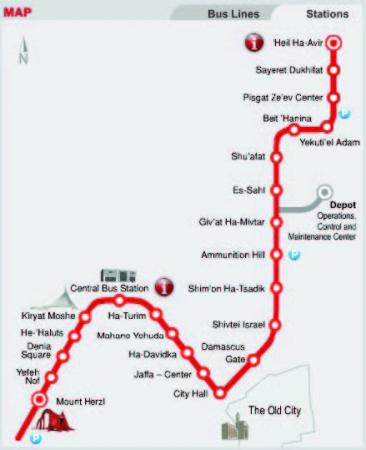

The line – controversial during its construction, because

of the years-long disruption to daily life and enormous

cost overruns – is 8.6 miles long, with 23 stops between

Mount Herzl, in the city’s southwest, and Pisgat Ze’ev,

a northeastern Jewish suburb built on land liberated by

Israel in the wake of the Six-Day War. Thus, it also serves

the Arab residents of East Jerusalem, as the tracks wend

their way past the Old City walls on the way to Jaffa Street,

in the heart of West Jerusalem’s city center; station names

are announced in Hebrew, Arabic and English, as they

scroll across LED screens in the cars – in the same three

languages. Trams are air conditioned, with large windows.

The section of the light rail which most interests tourists

extends between Mount Herzl – Israel’s equivalent of

Arlington Cemetery, also adjacent to Yad Vashem, the

international Holocaust Museum – and Mount Scopus,

the famous Har HaTzofim, with its spectacular views of

the Old City. A round-trip between the two ends of this

stretch takes about one hour and forty minutes.

Starting from the Mount Scopus end, the train passes

Ammunition Hill, site of one of the fiercest battles of

the Six-Day War, fought in June 1967. It is now one of

several official memorials symbolizing the reunification

of Jerusalem. Battleground fortifications have been

preserved, and an underground museum honoring the

fallen tells the story of the savage fighting.

Next comes Shimon HaTzadik station, named for the

location of the tomb of a High Priest during the time of

the Second Temple. Shimon HaTzadik Street is now a

“restaurant row” of good Arab eating establishments and

bars – where many young Jewish Israelis come to smoke

water pipes.

This whole area was no-man’s land between Israel and

Jordan in the period from 1948, when the State of Israel

was created, until the short 1967 war. Near Mandelbaum

Gate – Jerusalem’s “Checkpoint Charlie” during this 19-

year stretch – is the award-winning Museum of the Seam,

elucidating the “seam line” that now both divides and

unites the city’s Arab and Jewish sectors.

The elaborate Damascus Gate, or Sha’ar Sh’khem,

is one of the main entry points into the Old City – a

bustling market and shopping area between modern

East Jerusalem’s commercial district and the beginning

of the traditional Middle Eastern bazaar. At the other

end of this souk is Jaffa Gate, one of the three principal

entryways to the Jewish Quarter, the Western Wall and

the Temple Mount.

Continuing along the beautiful Old City walls, the train

runs slightly uphill, with the Notre Dame de Jerusalem

on the west side, opposite New Gate on the eastern side

(one of the few gates permitting vehicular entry to the Old

City). Built in the late 19th century as part of a French

complex of hostel, hospital and church, the Vaticanaffiliated

Notre Dame today is a hotel justly popular

with Catholic pilgrims. The hotel’s medieval-looking

towers are magnificent, similar to those of the nearby

Italian Hospital. The stunning views from the hotel’s

non-kosher rooftop restaurant rival those from its kosher

counterparts along King David Street.

Safra Square is the next stop, the access point for Jaffa Gate and home of Jerusalem’s City Hall complex. Most of the buildings in this area are from British Mandate times, including the Central Post Office and what was once the Anglo-Palestine Bank, recognizable by the still visible pockmarks from the Jordanian shelling of West Jerusalem.

Here, the tram begins to fill up: the center of the city can be very busy, often standing room only. You are now on Jaffa Street, Jerusalem’s main thoroughfare, and one of the city’s two main pedestrian malls, along with Ben Yehudah Street. The area is busy day and night, catering to patrons of the fine shops and restaurants representing most of the main cuisines known to mankind.

Just past the downtown triangle formed by Jaffa Street, King George Street and Ben Yehudah is Davidka Square, named after the crude artillery piece mounted in the plaza. Called the “secret weapon” of Israel’s War of Independence, it was not really very effective, and dangerous for operators; its one virtue was that it was noisy: the enemy ran whenever one was fired. A good place to get off for a snack is the next stop: the Mahaneh Yehuda open-air market. Still famous for its fresh produce, and free samples of halvah, it is now being transformed by the entry of trendy cafes and restaurants and gourmet shops.

Continuing westward along Jaffa, the train glides past some architectural highlights of the heart of the city: glorious buildings now being restored, many of which are slated to become expensive apartment complexes.

Just past the city’s Central Bus Station, the light railway traverses the “Bridge of Strings” or “Bridge of Chords”,

designed by the Spanish architect Calatrava. Said to be similar to a construction in Seville, its name actually derives from the musical instrument it symbolizes: David’s harp. The impressive bridge – visible for miles from Jerusalem’s western hills and highway to and from Tel Aviv – only used by the tram and pedestrians. (It also features as the cover photo for this issue of Jewish.Travel.)

After crossing the bridge, the train ascends Herzl Boulevard, taking us through the neighborhoods of Kiryat Moshe, known for its venerable yeshivas, and Beit HaKerem, one of the city’s original affluent suburbs. Finally, it stops at Mount Herzl, named after the father of modern Zionism, whose vision and drive was instrumental in the rebirth of the Jewish state. Sleek and peaceful, the tram is a perfect way to arrive.

The official website of the light rail system is:

www.citypass.co.il