When he visited Poland a couple of years ago, Michael Freund had no idea that he would accidentally make a historical discovery — never mind two.

By Michael Freund

Driving through the seemingly endless stretches of lush green fields and forested hills that cover southeastern Poland, it is easy to get swept away by the scenery.

The verdant soil and grassy meadows cry out with life. But then, like a jolt, comes the inevitable, as the memory of what once was, quickly crowds out the magnificent vistas.

I am on the way to Kanczuga, a town of just over 3,000 people located about halfway between the cities of Rzeszow and Przemysl.

It is a small point on the map, but it looms large in my family’s history.

Prior to the Holocaust, Kanczuga was at least 40 percent Jewish, with some accounts suggesting the figure was even higher. Until today, the official town seal continues to include a Star of David at its heart, as though in solemn recognition of the central role that Jews played for centuries in the life and vitality of this community.

But on the surface, there is nothing left of that vibrant past. Only memory remains.

In 1942, the Nazis and the Polish police rounded up Kanczuga’s 1,000 Jews. After being herded into the main synagogue, they were marched up the hill to the town’s Jewish cemetery and methodically gunned down. Locals celebrated by holding a picnic and cheering on the policemen as they opened fire.

All the life and the greenery around me suddenly fades away, receding far into the background as I ponder what became of our people.

The reason for my visit was simple: I had donated funds to restore the neglected cemetery in Kanczuga, and chose to attend the ceremony being organized by the local municipality to mark the occasion. What I didn’t expect

was that it would result in a very personal discovery as well as the recovery of Working in cooperation with Poland’s Chief Rabbi Michael Schudrich and the Warsaw-based Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland, we reached agreement on the scope of the restoration with Kanczuga’s mayor, who even paved a new access road at the town’s expense.

After the brief ceremony was over, I lingered, walking through the grounds and looking at the remaining tombstones. Suddenly, I chanced upon one with a familiar name: Freund. I was shocked and immediately called my father in New York and told him: “You’re not going to believe this but I’m standing here on the grounds of the cemetery in Kanczuga and I found a tombstone with the name Gittel Freund on it.” She seems to have been my great-great grandmother — one of many family members who remained in Poland.

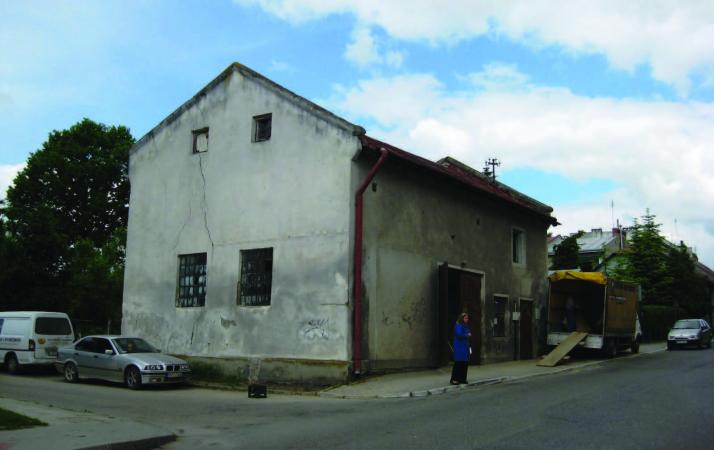

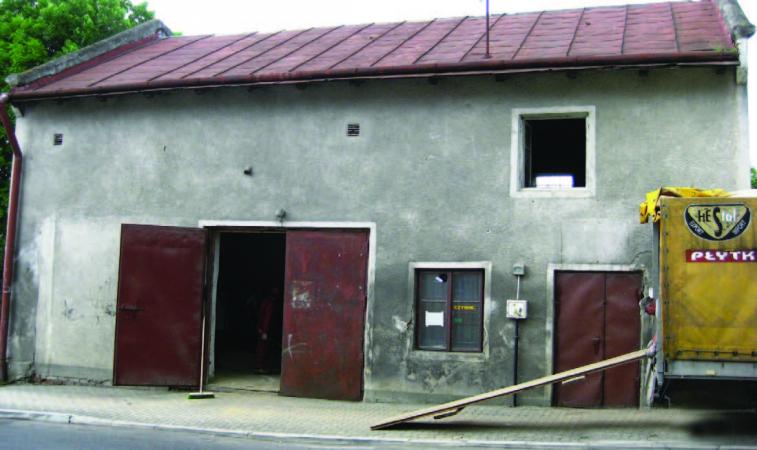

Deeply moved by this experience, I took out my handy map and some information gleaned from the web, and went back to the city center to locate a small building that once served as a synagogue. Inside, seven or eight local construction workers were busily tearing apart the insides of the structure, renovating it for the use of a local business. Piles of rubble and dust lay about, and large holes gaped through the ceiling, through which the original brick walls of the house of prayer were clearly visible.

As I walked through the mess, I could not help but notice the glares coming my way, as the workers looked at me, then at the yarmulke on my head, and then back at me.

Undeterred, I walked through the small structure, snapping pict ures, whispering a prayer and chapters of the Psalms, and wondering if this is where my ancestors poured out their hearts to their Creator.

Overwhelmed by the emotion of it all, I felt an inexplicable need to tell the workers what this building once was. For some strange reason, I wanted them to know this was a holy place.

One of the men seemed to speak a few words of English, and I managed to convey to him that this structure served as a synagogue prior to the war, and that my family had lived in the area. He smiled, somewhat awkwardly, before walking away, leaving me to wonder why I bothered to tell him at all.

But a few minutes later, as I was about to leave, the same workman approached me and tapped me on the shoulder. I turned around, unsure what to expect, when he handed me some yellowed, torn and dusty pages.

Immediately, I recognized the Hebrew text, and could not believe what I held in my hands. Pages from a siddur, from a prayer book, that had been lying here forsaken for more than 60 years. I shuddered as I thought of what must have happened to the last Jew who held this sacred object in his hands during the dark days of the Nazi onslaught. The workmen gathered around, pointing to the walls and to the ceiling, indicating to me that they had found these precious treasures as they ripped apart the inside of the building.

Grown men are not supposed to cry, and certainly not in front of others. But I couldn’t help myself, and the tears began to flow. I thought about all the loving hands the pages had passed through, how they had been studied, read and pondered by the Jews of Kanczuga who are no more. And then I thought that perhaps some members of my family had once handled these pages, which further fueled the sense of sadness and loss that I felt.

Part of me wanted to scream; to shout at the seeming injustice of the Jewish experience, but in some small way, I consoled myself, the memory of Kanczuga’s Jews would live on — not merely through these torn, yellowed pages, but more importantly, through me.

As one of them patted me on the back to console me, the rest went into the other room. Then, one by one, they came forward, handing me stacks of Hebrew pages — sections of Talmud, pages from Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah and portions of the Pentateuch and the High Holiday prayer service. They were of Kanczuga’s once-rich Jewish heritage, now reduced to lonely fragments hidden in the debris.

One of the workmen then went to sift through a large pile of rubble, searching for more pages to give me, which I took back to Israel for burial as tradition requires.

The men asked for nothing in return, and when it came time to leave, we shook hands. The foreman promised to collect any additional pages they might find and forward them to me through a local contact.

During my brief stay in Kanczuga, I had come face to face with the reality of Poland’s Jewish history and its untimely demise. So little remains of what was once a great Jewish civilization. But as I made my way back to the airport to catch a flight home to Israel, I couldn’t help but think: two generations after the Holocaust, we must do everything we can to ensure that their legacy lives on.

Michael Freund, an American-born Israeli, is chairman of Shavei Israel, a Jerusalem-based not-for-profit that exists

to strengthen ties between descendants of Jews and the Jewish People.

www.shavei.org